The Legacy Gift

By Dan Saevig

Barb Hogan’s son was a gift to family and friends.

Nearly 30 years later, Tom Hogan’s legacy is a gift to people he never knew. Many weren’t even born when he died in 1984.

Yet the memory of his life resonates every time a serious injury call is sounded in Northwest Ohio.

Barb is the mother of trauma medicine in the Toledo area. The traumatic death of one of her own gave life to formalized trauma care as we know it today, not only in this region, but throughout Ohio.

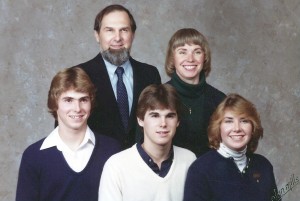

Energetic and enthusiastic, Tom was precocious by nature and a risk taker. His mom said that he gave her every grey hair she had. A junior at the University of Toledo, Barb and Al’s middle child was planning to switch his major from geology to recreational therapy because he was struggling with math.

Barb, who earned bachelor’s and master’s degrees from what is now known as UT’s College of Nursing and served for 15 years as a clinical professor of nursing at her alma mater, was a Life Flight nurse at Mercy St. Vincent Medical Center who had been on hundreds of runs. Al was in the midst of what would become a 30-year administrative career with UT’s library system.

With three college-aged children at home for the summer – older sister Kathleen was at UT and younger brother John was soon to transfer to UT from Miami University – Barb and Al were packing for a three-hour drive and a camping trip to Pinery Provincial Park on the shores of Lake Huron in Grand Bend, Ont.

“The last thing he said was, ‘Don’t worry about us, Mom,’ Barb recalled. “’We’ll be fine.’”

With that, Tom bounded down the stairs and off to his part-time job as a grounds maintenance worker at Laurel Hill Swim and Tennis Club.

To this day, it’s still not clear what happened the morning after Tom said goodbye.

A large ladder was hung horizontally on the ceiling in the club’s garage. Perhaps the ladder fell as Tom was taking it down. A more likely scenario is that the 21-year-old – a risk taker by nature – was performing chin-ups on the mounted ladder, something his boss had told him several times not to do.

This much is known.

Tom fell backward, his head striking the pavement. The force of the fall caused his head to snap forward. The ladder then landed on his face and his head hit the ground again. The neurosurgeon responsible for Tom’s care told Barb and Al that the reactive impact had sheared their son’s brain across its center.

“A few years ago, I hit black ice and was knocked unconscious,” Barb said. “I knew when I was falling that I was falling. But I couldn’t do a darn thing about it.

“But when I came to, I thought, ‘Well, Tom never experienced anything like this. Because he was gone when he hit, the minute his head hit the ground.’ It was kind of confirming for me when I got that head injury that he didn’t know what had happened and experienced no pain.”

A rescue squad was dispatched to Laurel Hill. Its crew had been trained in trauma care by Barb.

Tom was rushed to the Medical College of Ohio Hospital.

In Canada, a park ranger approached the Hogan camper and told the couple to call MCO immediately, that there was a medical emergency. This was in the days before cell phones, so the pair made their way to the public telephone in the campground registration area.

“I got one of the nurses I knew really well on the phone,” Barb said. “And she said, ‘Barb, we have your son here.’”

The words were devastating. When Barb shifted into emergency room nurse mode to find out the severity of the injuries, she was heartbroken.

Finally, she asked, “Which son is it?”

As that call was ending, another came from her co-workers at St. Vincent. Word of the accident had spread quickly. Life Flight and emergency room physician Randy King left his shift at St. V’s and went to MCO to help his co-worker.

“I said to Randy, ‘Don’t let them pronounce him (dead) until we’re there,’” Barb remembered. “Please don’t let them pronounce him.’”

Knowing that the first three days are critical when horrendous brain injuries occur, Barb and Al broke camp and quickly showered.

With water cascading upon her, Barb’s mind shifted from clinical nurse to mom. Tears began to flow.

A woman in the bathroom heard the heavy sobs and asked Barb if she was all right.

In her despair, Barb responded no, that she just got a phone call and she knew that her son was dying.

The complete stranger said nothing more, but stayed with the grief-stricken mother until she left the restroom.

Sometimes the best medicine doesn’t come with a prescription.

When the Hogans pulled their trailer into the parking lot at MCO later that day, they were met by more than 50 friends; emergency medical personnel who had worked with or been trained by Barb.

Sometimes the best prescription isn’t medicine.

“The way the community supported us was just amazing,” Barb said. “I think that was probably what made me so determined to see to it that everyone had that much of a chance.

“Not everyone has a whole community of people willing to stand with you and hold your hand when your kid dies.”

Tom had the best of care, but the pressure in his brain continued to rise. He passed away three days after the accident. His death came one month and five days after his 21st birthday.

Barb couldn’t do anything about her son. But there was something she could do, pledging to turn the worst thing that could ever happen to a parent into something good for others.

Trauma medicine in the 1980’s was in the midst of an exciting yet tumultuous period. Dr. John Howard, an MCO faculty member, was at the forefront nationally, authoring white papers to establish a national trauma structure based upon his experiences in the Korean War with MASH units, mobile army surgical hospitals.

At the same time, technology was improving and hospitals with helicopter capabilities were expanding their reach, serving outlying communities whose facilities weren’t able to treat the most severe injuries.

Yet the state of Ohio didn’t have formal guidelines for trauma care. The only group designating a hospital as a Level 1 trauma center – facilities equipped to handle the most seriously injured – was the American College of Surgeons. At the time, there were none in Northwest Ohio.

A founding member of the Society of Trauma Nurses, an international organization, Barb pushed for and was charged by St. Vincent management with establishing St. Vincent as a Level 1 facility.

“We started putting in place the people from within the institution that respond when a trauma comes,” Barb said. “That was a nurse from the operating room, a nurse from a critical care unit, the emergency room nurses, emergency medicine physicians, an emergency medicine resident, the trauma surgeon. Every person around that bed had a job that was written in the policy and procedures.

“Trauma case managers, social workers, the spiritual component of the hospital – pastoral care – were all part of the trauma team. The trauma case manager moved between what was going on in the room and the family, because my experience was all of those things were going to be really important for the mental health and…the eventual acceptance of whatever was going to happen in that trauma room for that family.”

Barb said that St. Vincent and MCO were verified as Level 1 trauma centers on the same weekend in 1990. ProMedica Toledo Hospital now also carries that designation.

With one fight won, Barb’s battleground moved to Columbus.

She was called to testify before the House of Representatives, joining other proponents of formalized legislation in support of a state-wide verifiable trauma system. Unlike others, she could speak, not only from a clinical perspective, but from a personal one, as well.

“What I said to them was, ‘My son died, but I had the ability to know that everything that could have been done was done,’” Barb said. “’He wouldn’t have lived no matter what trauma system was in (place). But that shouldn’t be a privilege. Everybody should have had that ability to say that.”

Barb celebrated her retirement from nursing in 2000 with the parallel announcement that Ohio legislators had mandated a verifiable trauma system that included a state registry of trauma care.

Now 73 years old, Barb was named the College of Nursing’s Alumna of the Year for Clinical Practice in 2013 and the recipient of the American Trauma Society’s Distinguished Service Award in 1997. Barb and Al have been married for 52 years.

Come July, 30 years will have passed since Tom’s death. It’s been said that time heals all wounds, but the tears in his mother’s eyes as she remembers her middle child says that the turning of the calendar has only helped close the wound. The scars still remain.

“Surviving such a loss is really hard,” Barb said. “You have to find a way to make sense out of it.

“’Why did it happen?’ There is no answer to that question. You ask the question, ‘Why? Why me?’ There is no answer to those questions.

“’How can we make something happen out of this that is good?’ I think that is where it all came from. ‘How do I cope? How do I deal with this?’

“It’s still very painful if I think about it so I don’t. I will miss him….forever.”

After his death, Tom was shared with the Toledo community. His skin was used to heal a child’s burn. His eyes and kidneys were also donated. The recipients were people he’d never met. They were presents of life from a young man who had died, yet perhaps no gift was more important than the establishment of a formal trauma system that has helped save the lives of thousands of critically injured patients.

In Tom’s death and Barb’s response, there is life.

It’s their legacy.