Toledo’s Rocket Man

by Patty Gelb

He’s a Rocket who writes about rockets.

Not necessarily The University of Toledo kind (although he has), but rather those that vault from launch pads spewing fiery rivers of flame en route to the vacuum of space.

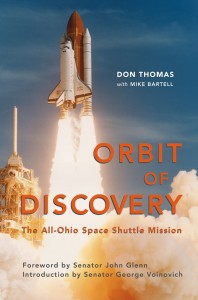

In fact, the latest chapter in his life — twelve of them to be more correct — is the recently published book, Orbit of Discovery, The All-Ohio Space Shuttle Mission, which he co-authored with NASA Astronaut Donald A. Thomas, Ph.D.

In fact, the latest chapter in his life — twelve of them to be more correct — is the recently published book, Orbit of Discovery, The All-Ohio Space Shuttle Mission, which he co-authored with NASA Astronaut Donald A. Thomas, Ph.D.

“It was a fascinating experience — one that I truly enjoyed,” says Mike Bartell (B.A. ’73), a veteran local journalist and long-time UT instructor in the Department of Communications who’s been interested in America’s space program almost since its inception which coincided with his childhood.

The book (406 pages published by the University of Akron Press) recounts the 1995 STS-70 mission aboard shuttle Discovery which was crewed by four native Ohioans, including the flight’s commander, Tom Henricks, who was born in Bryan and raised in Woodville; Thomas, who grew up in Cleveland; another from Cleveland/Bedford Heights; one from Troy (near Dayton), and a fifth from Amityville, N.Y. who was made an honorary Ohioan by then-Gov. George Voinovich.

The only other time in NASA history when there was an All-Ohio crew was in 1962 when John Glenn, of New Concord, flew by himself three times around the Earth aboard his Friendship 7 Mercury capsule.

Glenn wrote the book’s Forward; Voinovich penned its Introduction.

During the course of Bartell’s 35-year career at The Blade (he retired in 2008), he covered a number of space shuttle missions. STS-70, because of its Ohio connection, was one of them. The mission had another claim to fame. It was the only space shuttle flight that was delayed because a woodpecker drilled hundreds of holes into the foam insulation that covered the vehicle’s external tank necessitating extensive repairs.

“I thought this one mission was unique enough that I wanted to focus on that,” Thomas said. “It would highlight Ohio astronauts. I have a lot of pride in my home state and home town and I thought this would be a good focus for the book,” which he I had been working on for almost 10 years.

Orbit of Discovery also is Thomas’s autobiography — his early discovery of, which turned into love for, America’s space program, his laser-like focus to become an astronaut and his perseverance to achieve that goal despite numerous obstacles along the way.

Orbiting Earth for nine days, the STS-70 crew deployed a communications satellite, conducted a myriad of tightly scheduled scientific experiments, participated in media interviews including one with Bartell for The Blade, and documented a hurricane.

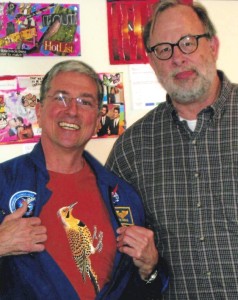

Shortly after the flight, Governor Voinovich invited the crew to join him at the opening of the 1995 Ohio State Fair. Voinovich also invited Bartell because he had written so much about the flight. That’s when Bartell met Thomas for the first time.

Over the years, Bartell periodically did brief telephone interviews with Thomas for shuttle-related articles, including those he wrote detailing Glenn’s return to space in 1998.

About 10 years later, Bartell was on hand when Thomas, representing the All-Ohio crew, presented one of Toledo’s ceremonial glass keys carried aboard Discovery during the STS-70 mission to the Toledo-Lucas County Main Library in downtown Toledo for permanent display in its children’s area.

About 10 years later, Bartell was on hand when Thomas, representing the All-Ohio crew, presented one of Toledo’s ceremonial glass keys carried aboard Discovery during the STS-70 mission to the Toledo-Lucas County Main Library in downtown Toledo for permanent display in its children’s area.

And four years after that, Bartell received the following email from Pat Damschroder, the UT Department of Communication secretary:

“Mike, a person by the name of Don Thomas just called and asked that I give you his cell phone number and have you contact him. He said that he needed to speak to you about publishing a book.”

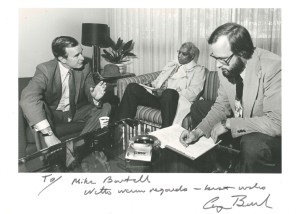

“I chose Mike because he was interested in the shuttle program and the space program,” said Thomas. “I knew he was familiar with our mission. And I knew he was a great writer — I knew he had that experience.”

Bartell, already retired from The Blade and edging toward retirement from UT, contacted Thomas and explained that he wasn’t sure he wanted to become involved in such a project. But he told Thomas to send him what he had written to that point. Soon a CD arrived and Bartell printed the contents to begin his review.

“It was single-spaced and it took up a loose leaf binder about this thick [holding his fingers apart representing a couple of inches],” said Bartell. “And, it wasn’t even 12-point type, I think it was 10-point type.”

He read what Thomas had written, detailed some suggestions for the book, and sent that information to Thomas, who admitted that what he sent Bartell was a manuscript written by an engineer.

“It was basically a data dump — every thought, everything I had put down on paper. Mike was the organizer, the filter to say you have too much here, you don’t have enough there. That was because of his writing experience that I am totally lacking in my profession as an engineer. And I needed him, from writing the first sentence in the opening chapter to saying ‘let’s take the woodpecker story and bring it to the front of the book.’ I had everything just chronological — we got assigned, we train, we fly. He had vision and ideas for the book right off the bat, and they were all good ones.”

Thus began an almost two-year collaboration that resulted in Orbit of Discovery.

“I have to admit I was very intimidated.” said Bartell. “I have never taken on anything that massive before — and it was massive. It took a lot of reorganization, a lot of rewriting, and a lot of additional writing. But I really believed in the project and I believed it had the potential to be a very good book.”

But it was going to take a lot of man hours to get the book ready for a publisher. “I think it was a bigger project than what he signed up for. But I think, in the end, it is a really good product,” Thomas said.

Thomas’ writing had a special quality that Bartell did not want to lose.

“When I read it in its raw version, I saw he had a wonderful conversational style of writing,” said Bartell. “It was like he was talking to you. I had a feeling that he wanted the reader to feel that they were there, experiencing what he was experiencing.”

Bartell and Thomas developed what they both described as an outstanding working relationship.

They did much of their work via telephone and email.

“We talked and emailed each other for a year and a half, three or four times a day,” Thomas said. “We had a really good working relationship and I think the best way to describe that is we started working on this as colleagues and he and I ended up as friends.”

“We talked and emailed each other for a year and a half, three or four times a day,” Thomas said. “We had a really good working relationship and I think the best way to describe that is we started working on this as colleagues and he and I ended up as friends.”

Thomas also came to Toledo several times for working sessions. Thomas loves Tony Packo’s, so the trips always involved several meals at that restaurant.

One thing that Bartell felt was missing from the book was Thomas’ personal story. Early versions of the book were specifically about the mission. Bartell told Thomas that he needed to tell his own story too.

“I told him, ‘You have a wonderful story about yourself and you need to share it,’” said Bartell. “I kept hammering him and it was like pulling teeth to get that information from him, but we finally got it. There were so many things in his life that were so fascinating to me — and, I think, to the reader. A lot of things came up just through conversations.”

For example:

“I said to him, ‘You never said how you met your wife. When he said very off-handedly that he met her on the Vomit Comet (a NASA airplane that simulates weightless and cause many participants to do what the nickname suggests), I said, ‘Hello, who meets their future wife on the Vomit Comet? We need to include that,’” recalled Bartell.

“Another time he casually mentioned that he was diagnosed with thyroid cancer shortly after he achieved his dream of being selected as an astronaut. That could have scuttled his astronaut career, but luckily did not. It was another of those ‘Hello, we need that in the book moments.”

Thomas originally had a different feeling about putting his personal story in the book.

“I was going to try to leave my personal story out,” Thomas said. “I was going to have it just about the mission. Mike said you have to put stuff about you, your wife, and your family. I was reluctant, but he was right and I think it became a better book because that.”

Thomas felt that Bartell brought so much to the book.

“Every sentence that Mike cut from my manuscript was like someone pulling my teeth,” Thomas said. “I thought ‘I wrote that sentence.’ Parts of it were painful, but rightly so. I had 53 pages detailing the foam of our external tank. Mike told me that was too much detail.”

Bartell not only helped organize the book, pull the personal story from the astronaut and cut back on some of the detail, he also gave Thomas a lesson in the use of punctuation.

“Mike and I did clash on one thing,” Thomas said. “Throughout the book originally I had like 10,000 exclamation points. Everything was exciting and I wanted to emphasize that. I didn’t end a sentence with one exclamation point, but sometimes two, three or four. He straightened me out saying you can’t do that. So back and forth — even today when he sends me an email — he will frequently end it with 10 or 20 exclamation points. He did leave a few in the book, but not many.”

Thomas felt that it was Bartell’s expertise in refining the story that made the book turn out the way it did.

“I would send him a chapter I had worked on and he would rewrite it and send it back to me,” Thomas said. “I would just say ‘wow.’ I always said wow when I got things back from him. It is my story and he wanted to keep it in my voice, but the polishing he was able to do on it, every time I got it back I would always say ‘Wow, that’s great. That is why you are a writer and I am an engineer.’”

And it was a great experience for Bartell as well.

“It was really a fascinating experience helping to put it together,” said Bartell. “But it is truly Don’s book — not mine. I’m just pleased with how it turned out.”

The paths of both of the book’s authors were determined early in life. Born around the same time, they avidly followed in newspapers and on television reports about the space program. That helped them decide their futures — Thomas wanted to be an astronaut and Bartell wanted to write about people like Thomas and their exploits.

“I’ve always told people that I was born about 30 years too late,” said Bartell. “I would have rather covered the early days of the space program than the later years, but at least I got to cover the space program.”

Bartell’s trajectory toward journalism also was heavily influenced by his father’s career. Frank J. Bartell (B.BA. ’43) was a wire service and newspaper reporter.

“I found stuff where Harry Truman made a whistle-stop trip through Toledo when he was running for president in ’48,” said Bartell. “My dad was working for United Press International and he covered that. I found references to my dad being at the train station for that event.”

Bartell’s father later became a partner at a very large public relations firm and he often involved Mike in his work. Young Bartell was used several times as a model, or “a prop” as he affectionately described it, for publicity pictures.

He had an early look at broadcasting when during the summer of 1960 he joined Gordon Ward, the news anchor of WTOL-TV at the time, for a television commercial. There was no videotape in those days. It was done live on numerous occasions that summer.

He also got a behind-the-scenes look at The Blade, radio stations and other TV stations in his teens working weekends, summers and school vacations at his father’s office as a messenger boy. His responsibilities included dropping off news releases at the media outlets, and Bartell often found himself in various newsrooms around the city. He told the receptionist at The Blade during one of his deliveries that he would work there one day.

Bartell was a member of the staffs of his high school newspaper and yearbook while attending what is now St. John’s Jesuit.

It was not a tough decision figuring out where he wanted to go to college. He never entertained going anywhere other than The University of Toledo. He followed in the footsteps of his father and his brother, Frank J., III (B.A. in Biology, Sociology and Economics in ’69 and more commonly known as Jack). Bartell knew he wanted to go into journalism and UT’s journalism program was incredibly strong. While at UT, he worked on the school’s newspaper, The Collegian, beginning as a reporter, then becoming the news editor, and finally the managing editor.

“The really neat thing about working there was I met people who have remained lifelong friends,” said Bartell.

He left The Collegian when he was hired as a reporter at WSPD Radio during his sophomore year. He maintained his full-time student status while working full-time at WSPD. He did reporting and wrote stories for the newscasts. He was a ghost writer for local radio news legend Jim Uebelhart, which Bartell said was a fabulous experience because it was a one-on-one tutoring situation for him.

During Bartell’s senior year at UT, he was offered a full-time general assignment reporter position at The Blade, beginning his career at the paper.

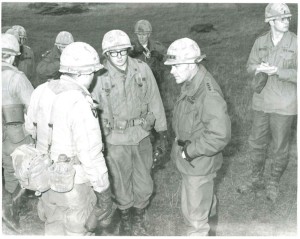

Although his path seemed set, there was one planned detour before settling into The Blade. Going into the military was a Bartell family tradition. His father was in the Navy during World War II, his brother was in the Army, and he was in ROTC while attending UT. It was during the Vietnam War-era and even though Bartell’s draft lottery number was 004 — the only lottery, he noted, that he ever won — he had planned on serving anyway and was commissioned as an officer in the U.S. Army in 1973 following his graduation.

Although his path seemed set, there was one planned detour before settling into The Blade. Going into the military was a Bartell family tradition. His father was in the Navy during World War II, his brother was in the Army, and he was in ROTC while attending UT. It was during the Vietnam War-era and even though Bartell’s draft lottery number was 004 — the only lottery, he noted, that he ever won — he had planned on serving anyway and was commissioned as an officer in the U.S. Army in 1973 following his graduation.

Bartell spent most of his time in the military in Germany as a platoon leader, company commander, and then on the staff of the commanding general of the 8th Infantry Division. While he felt his time in the military was a good experience, he never lost his taste for journalism.

Bartell spent most of his time in the military in Germany as a platoon leader, company commander, and then on the staff of the commanding general of the 8th Infantry Division. While he felt his time in the military was a good experience, he never lost his taste for journalism.

When he was leaving The Blade to go into the military, one of his editors told him that he would have his choice of where he wanted to go when he returned. He was experienced in public relations as well as broadcast and print journalism.

“He told me I would never go into public relations,” Bartell said. “He said I enjoyed the chase too much and there is no chase in PR.”

Tracking down a story and telling people about it was Bartell’s passion. He did enjoy the chase. So when he left the military in 1976, he returned to The Blade.

“I loved the immediacy of broadcast journalism, but I liked the depth and detail of print journalism,” said Bartell. “So I sided with the depth and detail. You get to tell a more in-depth story to people rather than short snippets.”

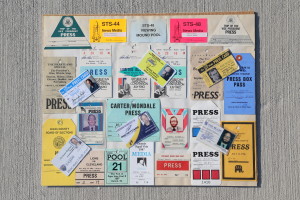

His writing resume at The Blade reads like a history of the big stories in Northwest Ohio and Southeast Michigan over the last 35 years.

His writing resume at The Blade reads like a history of the big stories in Northwest Ohio and Southeast Michigan over the last 35 years.

Be it good or bad, mundane or unusual, Bartell wrote about it — crime, fires, accidents, government, courts, politics, education, presidents, and a pope.

His coverage of a stolen painting from the home of Toledoan Lyman  Spitzer led to the recovery of one of the world’s most famous painter’s works. Bartell felt there was more to the robbery but the Toledo Police didn’t think it was a particularly big deal. Upon research, Bartell learned it was a Picasso and his page one story led to the involvement of the FBI. The painting was recovered in San Francisco a few days later.

Spitzer led to the recovery of one of the world’s most famous painter’s works. Bartell felt there was more to the robbery but the Toledo Police didn’t think it was a particularly big deal. Upon research, Bartell learned it was a Picasso and his page one story led to the involvement of the FBI. The painting was recovered in San Francisco a few days later.

In 1977, Bartell was named the paper’s education writer during Toledo Public Schools’ financial crisis. Voters kept rejecting operating levies forcing the district to, several times, close all of its buildings for weeks at a time. Bartell was working on a story about the situation when he called each of the TPS board members. In what he thought would be a throw-away question at the end of each conversation, he asked the board members “Do you still have confidence in the superintendent?”

Four of the five board members — a majority — said no. Bartell wrote the story, and the long-time superintendent, Frank Dick, resigned the next day.

“I had people call me afterward and congratulated me. I took no satisfaction, however,” said Bartell. “I realized that I negatively impacted that guy’s life. Did it need to be done? Apparently. But did I take any great pride in it? No. I felt it was just a story that I had to tell.”

During the famous Blizzard of 1978, Bartell was at the forefront of The Blade’s coverage because he was one of only a few people who had a four-wheel drive vehicle at the time. He wrote the front page story on the first day of the massive weather event, after being told by the newspaper’s managing editor to remember that “today you are writing history.”

On day two of the blizzard, conditions deteriorated. Bartell recalled driving to The Blade in the early morning darkness with another reporter telling him to speak up if he saw anything on the road in front of them. When the passenger nervously asked him if he was watching the road, Bartell replied that he wasn’t. He was watching the street lights because that was the only way to know that he was even still on the road.

Bartell spent the whole blizzard transporting staff members to work, taking photographers out to document the event and writing stories of the effects on the community. He even talked himself aboard an Ohio Army National Guard helicopter to become the first reporter to fly over the area, giving readers a bird’s eye view of the storm’s aftermath. He had worked 84 hours straight and was told by his editor to go home and get some rest.

Bartell spent the whole blizzard transporting staff members to work, taking photographers out to document the event and writing stories of the effects on the community. He even talked himself aboard an Ohio Army National Guard helicopter to become the first reporter to fly over the area, giving readers a bird’s eye view of the storm’s aftermath. He had worked 84 hours straight and was told by his editor to go home and get some rest.

“But the blizzard became the bane of my existence,” said Bartell. “Every time there was an anniversary, the fifth year, the tenth year, etc., I would hear ‘write a story about the blizzard.’ Well it was the same story. It didn’t change. Ultimately, the blizzard had become boring.”

A few months after the blizzard and after Toledo Public Schools passed an operating levy, district personnel went on an over 30-day strike that closed all the district’s schools. Bartell covered the story relentlessly and by the time the strike was over, he was hospitalized for 10 days.

“I thought I had a bad cold, but I really had mononucleosis. I ended up off work for several months,” said Bartell.

Over the years, Bartell was the reporter assigned to cover Ronald Reagan’s 1980 presidential campaign. During Pope John Paul II’s 1987 visit to Detroit, Bartell was chosen by the Archdiocese of Detroit as a pool reporter which got him up-close with the pontiff.

Over the years, Bartell was the reporter assigned to cover Ronald Reagan’s 1980 presidential campaign. During Pope John Paul II’s 1987 visit to Detroit, Bartell was chosen by the Archdiocese of Detroit as a pool reporter which got him up-close with the pontiff.

Bartell’s knowledge of the space program helped Ohio dodge a major mistake on its commemorative quarter. He noticed that the astronaut in proposed coin’s artwork was meant to depict Ohio native Neil Armstrong, the first man on the Moon. But Bartell realized that it was based on a photograph that those involved in the coin’s design thought was Armstrong, but instead was Edwin “Buzz” Aldrin, a New Jersey native who was the second man on the Moon.

At any rate, the use of that picture-derived artwork would have been a violation of U.S. Mint policy forbidding the image of a living person on a U.S. coin.

As the result of his article detailing the matter, the mint redesigned Ohio’s coin.

As the result of his article detailing the matter, the mint redesigned Ohio’s coin.

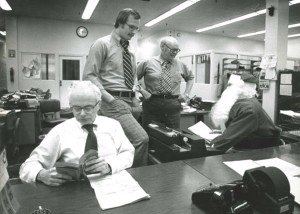

Over the years, Bartell rose through the ranks at The Blade. He twice served as the paper’s night city editor (1981 to 1983 and 1992 to 2008) responsible for the local news, managing the night reporting staff, choosing photos, editing stories and laying out pages.

In 1990, he was named the assignment editor and was responsible for helping set the tone of the paper. He still wrote and reported in addition to all of his other responsibilities.

“It’s a little bit cliché, but Mike was like one of the last hard-bitten editors of The Blade and I say that in a positive way,” said Dave Murray, Managing Editor of The Blade. “He really had standards for how reporters should report and how reporters should write. I kind of miss him in a way because nobody today is like Mike and the people before him.

“He really demanded that the reporters do it right. He would bring them over and show them what went wrong and the way to do it right and that is invaluable in a newsroom. Mike was there to teach as well as edit. It was a loss when he left The Blade — it was a loss for us,” said Murray.

When The Blade decided to become a morning newspaper in 1992, Mike began his second stint as night city editor because of his knowledge of production and his strengths as an editor. He held the post for 16 years, a tribute to his abilities.

He recalled the story about Carty Finkbeiner’s suggestion of moving deaf people to homes near the airport. Other staff at The Blade didn’t think it was that big of a deal, but Bartell realized that it was front page news. After an evening of debate among senior editors, the story was moved to page one and once reported by The Blade, Finkbeiner’s suggestion became a national story.

“Mike is a great guy and in his journalism career at The Blade, he made a difference every day,” said Kurt Franck, Executive Editor of The Blade. “As a matter of fact, since his retirement, we’ve lost a lot of our institutional knowledge because of his background, working in Toledo and understanding the things that go on in Toledo. When we needed something, we could always go to Mike and he would have it at his fingertips right away because it would come right out of his brain and it would be very helpful.”

When asked what he considered the biggest story of his career, Bartell said he really didn’t have an answer for that. He felt each story had its own merits.

“It was gratifying when you broke a story that nobody knew about,” said Bartell. “Or, more in particular, if a politician or government official didn’t want you to know about. That was immensely gratifying.”

“There were just so many things that I found interesting. We had a notorious bag lady who lived downtown named Elaine Higgins. She had issues, caused trouble downtown and I wrote a lot about Elaine. One of the things that would absolutely fascinate me is I would be walking down the street and Elaine would stop me. She would either compliment me on the article that I had written about her or be very critical of the article, but she was reading my stuff.”

It was in 1981 during his first go-round as night city editor when Bartell received a phone call that added a new dimension to his life. His collegiate alma mater asked him to teach a news writing course. During that time, it was common for UT to bring local journalism professionals in to teach courses and Bartell was honored to be asked.

“I had just started as the night city editor and thought it would be something to do during the day during the winter,” said Bartell. “Then they asked me back the next semester, then they asked again, and again, and again. I never, ever anticipated being at UT for 32 years.”

During his years as a student at UT, he was taught by many Blade staff members and remembered how influential and beneficial those courses were. He was excited to have the opportunity to mentor others during his teaching career.

His courses were very popular over the years and always filled up quickly. He taught courses in news writing, news reporting, introduction to communications, industrial-technical writing, and supervised several independent studies.

Dr. Paul Many, a now retired professor of the UT department of communication, had the opportunity to work with Bartell over the years.

“I can say that Mike is a very dedicated person,” Many said. “He taught for us in the department part-time over many years. None the less, he spent a lot of time working with students. One of the most concrete images of Mike is him sitting in class next to a student working with them on a problem or project. He certainly brought a lot of experience into the classroom which is invaluable. There is a saying that ‘there are no great gods of news writing’ meaning that there was always some variation on the way news can be written. So I would say ‘there are no great gods of news writing…except for Mike Bartell’ because he was so knowledgeable.”

Bartell loved teaching and it never felt like work to him.

“I was at a gathering of a group of friends one time and a person I didn’t know well asked me what my hobbies were,” said Bartell. “Before I could respond, one of my friends immediately answered ‘teaching’ and I realized that was so true. Teaching was never a job to me, it was always kind of a hobby. I loved working with the students. I remember walking across campus and remembering walking there as a student, but now I was a teacher. I thought that was pretty incredible.”

In 2005, the UT department of communication named Bartell its outstanding alumnus. But his proudest accomplishment at UT came in 2012 when he was presented with a UT Student Impact Award. The award comes from the most important constituents for professors — their students. The selection is based on personal nominations highlighting ways they have positively influenced students through enthusiasm, knowledge, dedication and creativity.

“That award came straight from my students,” said Bartell. “That really meant a lot to me.”

One of the anonymous student submissions nominating Bartell for the award illuminates what made him such a great teacher:

“Without the mentorship and education I received from Mike Bartell, I can honestly say that I don’t know where I would be right now. He helped me realize my dreams, and then encouraged me to pursue them. He is more than a professor. He changed my life, and I am forever thankful to him for that. He deserves this award not only because of what he did for me, but because of what he does for each and every one of his students. He is invested in them and cares about their future, and that is a trait every faculty member should exhibit.”

Bartell loved his time as a professor and always gave above and beyond for the students.

Danielle Gamble, a former student of Bartell’s, became inspired by journalism after working at The Independent Collegian, UT’s student newspaper that formed from The Collegian in 2000. Bartell was serving as a mentor at the paper he wrote for as a student because they did not have an advisor then. Gamble, a music major at the time, was considering changing her major during her third year and approached him for advice.

“After only about a month of knowing each other, I stood outside in a parking lot with Mike and had a conversation about what I should do,” said Gamble. “After listening intently to me laying out my feelings, Mike assured me that I had the ability to do it, and encouraged me to go for it. I can still see him in that parking lot, giving me the pep talk and the push I needed.”

Gamble graduated in spring of 2014 and now works for The Independent Collegian as the general manager and adviser.

“It’s a conversation that changed my life, absolutely and magnificently,” she said.

Dr. Richard J. Knecht is a professor emeritus of communication and has taught at UT since 1971. He was the department chair over a 10-year period and held that position when Bartell was teaching for the department. Knecht nominated Bartell for a Press Club of Toledo award, not only for his contribution as a teacher but also as a full-time professional in the community.

“He is the only adjunct faculty member that I know of, that actually came and held office hours for students. He would come in on a designated day and work with the students so they would have advancement in the class. He was a mentor to these individuals. As the night editor of The Blade, he was able to bring that experience to the class. Students were very fortunate to have a full-time professional in the classroom with them who was really dedicated to teaching,” Knecht said.

Bartell, when asked what he will be doing now that he is finished with the book and retired from UT and The Blade, replied laughingly, “whatever the heck I want.”

Bartell did share he has another book in the works. When asked what it was about, he said with a grin, “I am not telling you. The research is done and all I need to do is sit down and write it.”

However, he did offer a hint.

“It’ll be about Rockets — not the kind that go into space!”

To order Bartell’s book, click here.