A Taste of Patience

by Patty Gelb

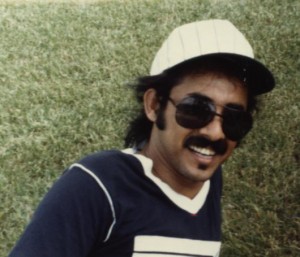

We have all heard stories about the damage that can happen when a car collides with a large deer. Imagine the damage a camel standing seven feet tall and weighing upward of 2,000 pounds could cause. Mohamed Eid Al-Araimi (’81 with a B.S. in Industrial Engineering) doesn’t need to imagine it. He experienced it firsthand.

We have all heard stories about the damage that can happen when a car collides with a large deer. Imagine the damage a camel standing seven feet tall and weighing upward of 2,000 pounds could cause. Mohamed Eid Al-Araimi (’81 with a B.S. in Industrial Engineering) doesn’t need to imagine it. He experienced it firsthand.

Al-Araimi said goodbye to his new wife of less than a year before heading for what was supposed to be his last week, ending 10 months of training in a remote area of Oman. Little did he know that it would be the last time he spoke to his wife before the tragic accident that would leave him paralyzed for what is now 33 years, changing his life forever.

Al-Araimi was driving from his hometown of Sur, the capital city of Ash Sharqiyah in the northeastern region of Oman. He was working for Petroleum Development Oman having returned from the United States one year earlier, where he studied at The University of Toledo to become an industrial engineer.

Al-Araimi was driving from his hometown of Sur, the capital city of Ash Sharqiyah in the northeastern region of Oman. He was working for Petroleum Development Oman having returned from the United States one year earlier, where he studied at The University of Toledo to become an industrial engineer.

“It was an incredibly dark night with no moon and a pitch black sky,” said Al-Araimi. “I was somewhere along the 200-mile stretch of the Sur-Muscat road, early at dawn when the light was just making an appearance announcing the birth of a new day when my life took a turning point,” he said.

Two camels suddenly crossed the road several yards ahead of him.

Driving 65 miles an hour, Al-Araimi had a split-second decision between three options to try to avoid disaster. He could swerve to the right and possibly roll over, falling into the valley below. He could go to the left of the camels and collide head-on into a car coming from the opposite direction. He chose the third option.

“I slammed the brakes and prayed humbly to God that the car would stop before colliding with the two frightened camels,” said Al-Araimi. “But the car kept sliding, crashing into one of the camels.”

The camel flew through the air, landing with its body smashing through the roof of Al-Araimi’s car.

When he regained consciousness, he felt as if his head was separated from his body. His hands let him down when he tried to unfasten his seat belt. At that moment he thought about his wife. A song was playing on the car’s tape player that was one of his wife’s favorites.

When he regained consciousness, he felt as if his head was separated from his body. His hands let him down when he tried to unfasten his seat belt. At that moment he thought about his wife. A song was playing on the car’s tape player that was one of his wife’s favorites.

“Although the player was only a hand-reach distance away, it seemed that it was coming from a place that does not exist,” said Al-Araimi. “I prayed to Almighty Allah to shelter me with His blessings and to make this shock an easy one for my family to bear.”

This was the beginning of a very long journey that changed Al-Araimi’s life, turning him from an engineer into a novelist and short story writer.

Al-Araimi was born in a small village of Wadi Murr, which is located in the eastern fringe of Ruba al-Khalil desert in Oman. The village name, Murr, is the Arabic word for bitter. It is also the name of the myrrh plant, which grows in Arabia. The inhabitants of the village are called Bedouins (settled nomads) which in Arabic means ‘the dwellers of al-Badiyah’ (the desert).

In Wadi Murr, his life revolved around camel herds and caravans. Living in the desert with the everlasting struggle to survive in one of the harshest environments in the world demands a very specific set of values, structures and family dynamics.

In Wadi Murr, his life revolved around camel herds and caravans. Living in the desert with the everlasting struggle to survive in one of the harshest environments in the world demands a very specific set of values, structures and family dynamics.

“The social life of our village, though harsh and remote, lacking all modern facilities and surrounded by the apparent emptiness of vast sand dunes and barren gravel plains, was not as tedious as one would expect,” he shared of his childhood. “On the contrary, it was a vigorous life, full of joy. Although I did not learn writing and reading during my childhood years, the desert taught me how to hold, aim and trigger a rifle. There I was raised to fear no wolf and to defend my family and our livestock in the absence of my father. It was a place where living was easy and simple; it was people, where everybody knows everybody.”

When Al-Araimi was 10 years old his family moved to the coastal city of Sur. His father decided to take him on the family merchant ship that traveled the Arabian Sea from Basra in Iraq to Eden at the southern edge of the Arabian Peninsula. It was on these voyages that Al-Araimi started his education.

“On the deck of our ship I started learning reading, writing and some mathematics,” said Al-Araimi. “I became a merchant of my own when my father gave me 10 ryals ($ 26) to start my own business by buying and selling foodstuff from and to villagers along the coast of Arabia. From there I spent 10 years moving from one city to another in the Arabian Gulf seeking better education.”

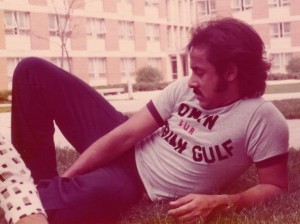

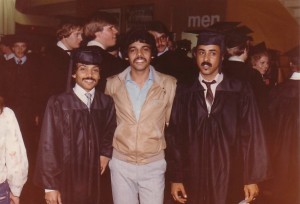

When given the opportunity to continue his education he was given the chance to choose between England and the U.S., he chose America. He first went to Findlay College where he spent two quarters learning English before coming to UT.

“Well it is America, land of chances and opportunities,” Al-Araimi shared. “During the time I was at Findlay College, I used to visit friends of mine in Toledo and also we used go there for shopping and other entertainments. Therefore, when I had to move from Findlay College to a university to begin my engineering study, I thought of UT and Toledo as a place to study and live. I spent three and a half years in Toledo and obtained a Bachelor of Science in Industrial Engineering.”

He remembers his short time in Toledo and America with fondness. While here, he traveled quite a bit, visiting many cities in Michigan. He also went on a driving trip down to Florida, camping in parks along I-75. He took a camping trip where he visited the Smoky Mountains and recalled a 54-hour straight driving trip with three friends from Toledo to Portland, Oregon.

“Special memories of my time at UT include enjoying the climate of the summer season where the sun light lasts until 10 p.m.,” said Al-Araimi. “I used to go with friends for picnics at Ottawa Park and spent time there playing tennis, volleyball and other entertainment activities. There was a Greek restaurant downtown that I often went to with a friend and I also used to eat grilled fish in a good restaurant located in the Student Union. Near where I lived there was a mall where I used to go to take a late breakfast during weekdays. I enjoyed eating dates with coffee. It used to remind me of my mother’s breakfast.”

When he returned to Oman after graduation he married the girl he fell in love with, Fatimah. Six weeks after his marriage he got a job with the oil company Petroleum Development Oman with a position in the oil fields in the Omani desert. It was nine short months later, almost the completion of his training, when he had his accident.

When he returned to Oman after graduation he married the girl he fell in love with, Fatimah. Six weeks after his marriage he got a job with the oil company Petroleum Development Oman with a position in the oil fields in the Omani desert. It was nine short months later, almost the completion of his training, when he had his accident.

Immediately following the accident Al-Araimi was placed in plaster casts from his neck to his lower abdomen.

“When I regained full consciousness at Khoula Hospital, I realized how serious my injury was,” said Al-Araimi. “I could now see that the upper part of my body was wrapped in a plaster cocoon from the chin to the lower part of my abdomen with tubes going in and coming out of the lower half.”

The preliminary diagnosis was that his injuries were relatively minor and that he would be coming home soon. Fatimah believed this good news and prepared their home for well-wishers and visitors who she expected would stop by to visit. It did not take long for that positive feeling to change among the whole family.

After several weeks of tests, x-rays and waiting, the doctors came to Al-Araimi with the final diagnosis. The injury to his spinal cord had impaired his nervous system causing all parts of his body below the injury to be cut off from his brain. The nerves of the spinal cord had become unable to transfer messages from his brain to his muscles. The doctor told Al-Araimi that the injury was unable to be repaired that he would never resume normal functions again.

“As the doctor tried to refer to paralysis without actually using that term, I relieved him from the trouble of breaking the news and explaining my critical situation to me,” said Al-Araimi. “I said to him ‘Don’t bother yourself. I understand my current state of health and its consequences for my future. However I have some questions which I would like you to answer if you don’t mind.’”

Al-Araimi thought that the doctors felt he didn’t fully grasp the implications of what they said, but he understood them.

“One might have expected a more bitter reaction, reflecting the extent of my injury,” said Al-Araimi. “My dreams suddenly vanished, destroying all that I had built since I left my village behind seeking to make something of myself. It was fully expected that I would cry hysterically and go into denial. It is true that I did not react in such a way, but I was fully aware that pain and sorrow would be my companions for the rest of my life.”

The first two months following his accident, he was encased in the plaster casts. Petroleum Development Oman arranged for specialized treatment in England in a hospital that specialized in spinal cord injuries. The day he was leaving his homeland, he said goodbye to his wife holding back his tears.

“I tried to be strong for her sake, just as I had attempted to do so when I had met her for the first time following my accident. I don’t know how I managed to curb my feelings and prevent my own tears from flowing…maybe it was due to her insistence that I see her smile before I departed. Despite the customs of our traditional society and the presence of so many people, she kissed me on the forehead without any hesitation, smiling and weeping as I was about to be carried inside the ambulance.”

“I tried to be strong for her sake, just as I had attempted to do so when I had met her for the first time following my accident. I don’t know how I managed to curb my feelings and prevent my own tears from flowing…maybe it was due to her insistence that I see her smile before I departed. Despite the customs of our traditional society and the presence of so many people, she kissed me on the forehead without any hesitation, smiling and weeping as I was about to be carried inside the ambulance.”

Al-Araimi was transported on a stretcher that was created especially for the trip. He was strapped with belts suspended about two feet from the ceiling of the plane. He spent his time on the plane exactly as he had done at the hospital, looking at the ceiling or shutting his eyes.

On the day of his arrival at Paddocks Hospital in England about 30 miles from Heathrow Airport, his doctor reviewed his reports and immediately instructed the staff to remove his plaster casts much to Al-Araimi’s relief.

He spent the next nine months at Paddocks as part of his rehabilitation process. He learned how to function to the best of his ability, including being moved into a wheelchair. He learned how to carry out routine personal activities such as using a toothbrush and eating with the aid of some special tools. Part of the rehabilitation process also involved learning how to write and print which would allow him to have a professional career again.

“No words can adequately express the meaning of loss,” said Al-Araimi. “Of losing everything suddenly, finding oneself unable to even hold a pen or use other tools. I started to relearn the fundamental daily activities that parents teach their children during their early years.”

When his doctor announced that his treatment was about to end, he felt both joy and fear.

“I was happy to see my wife and family and scared of the uncertain future and the heavy burden that my disability would impose on them,” said Al-Araimi.

“I was happy to see my wife and family and scared of the uncertain future and the heavy burden that my disability would impose on them,” said Al-Araimi.

While in the UK, he had spoken with Fatimah frequently to prepare her for what she should expect. He had a long frank discussion with her to explain where he was in the rehabilitation process and what his life would be like upon his return.

“I truly believed that she would find it difficult to deal with me, both physically and psychologically,” said Al-Araimi. “As it turned out, my suspicions were unfounded. Fatimah’s love for me gave her an infinite ability to face the challenge of my new self. Her love, demonstrated by the way she treated me, simply melted away my fears. She planted the seed of hope in my spirit and lit many candles to illuminate the dark future I had anticipated.”

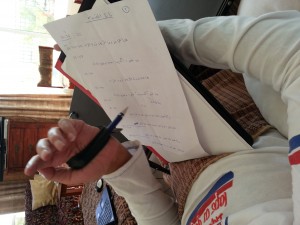

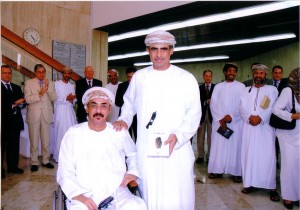

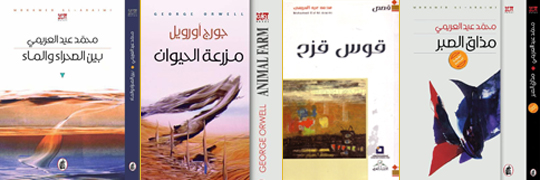

Thirty-three years have passed since Al-Araimi’s horrible accident and much has happened in his life. He still works for Petroleum Development Oman but now as a translator instead of an engineer. He has also authored several books and short stories including the book “A Taste of Patience” that documents his tragic accident, the rehabilitation process and where he is in his life today. He writes using a leather strap with Velcro, wrapping it around his hand and to a pen or small stick which he says he has no difficulty using.

Thirty-three years have passed since Al-Araimi’s horrible accident and much has happened in his life. He still works for Petroleum Development Oman but now as a translator instead of an engineer. He has also authored several books and short stories including the book “A Taste of Patience” that documents his tragic accident, the rehabilitation process and where he is in his life today. He writes using a leather strap with Velcro, wrapping it around his hand and to a pen or small stick which he says he has no difficulty using.

“During my drive to improve my translations skills, I gained and developed some writing tools,” said Al-Araimi. “I wrote a few short stories and articles published in local newspapers; I did not take writing seriously. The turning point in my writing experience came when I published an article titled ‘Living with Disability’ which was widely received and appreciated. I was encouraged to expand it to a book. The book ‘A Taste of Patience’ had extensive media coverage in Omani mass media and some Gulf newspapers. I felt really good knowing that I have entered the world of writing, though very late, with a strong start and great recognition.”

His goal with writing the books was to share that being disabled is not the end of life. It does not mean surrendering to its terms, but rather making the best of what you got to lead a new life with new hopes, new dreams and new ambitions.

“Since my accident, my daily life was nothing but a continuous struggle between an exhausted body and a strong will that refused to give up yet,” said Al-Araimi. “I’m not a hero, nor do I seek heroism. It’s only a feeling of self-esteem that supported me to overcome my disability. I have achieved another victory by living through such a long period coping with my disability and its cruelty. I have done so by clinging to the hope that tomorrow will be better than today, just as yesterday was better than the day before.”

The inspirational book “A Taste of Patience” can be purchased at Amazon by Clicking Here.

To learn more about the other books that Al-Araimi has written or to read more about his life and see his poems and short stories, click here to visit his website.