An unforgotten history

Rocket athlete, Korean war hero brought tenacity to challenges

By Laurie B. Davis

Ronald Spilis (Bus ’56, ’64) has always been athletic. At Central Catholic High School, he ran track and played football for four years, until he graduated in 1948. He gained letters in both sports, but also lost a few front teeth on the football field.During those teenaged years, other young men had come back home to Toledo as World War II veterans. Spilis’ future would find him playing football with some of those young men as fellow University of Toledo Rockets. He also would one day take a walk in their boots on the terrain of a battlefield.

Spilis became a Rocket, but not until an injury derailed his original plans. At 17, Spilis jumped on a Greyhound bus headed for Youngstown, Ohio, where he had high hopes of once again playing ball, this time with a college team. “I had the opportunity to go to Youngstown University. I took advantage of that because it was supposed to be a good program with a good coach. It was my ambition at the time, and my desire to play football,” says Spilis. “I can remember the coach. His name was Beede.”

When the players got their uniforms, practice commenced. “We practiced very diligently and hard, and to my dismay, I chipped a bone in my ankle during practice.” The injury closed one door and opened another.

Bound for Home

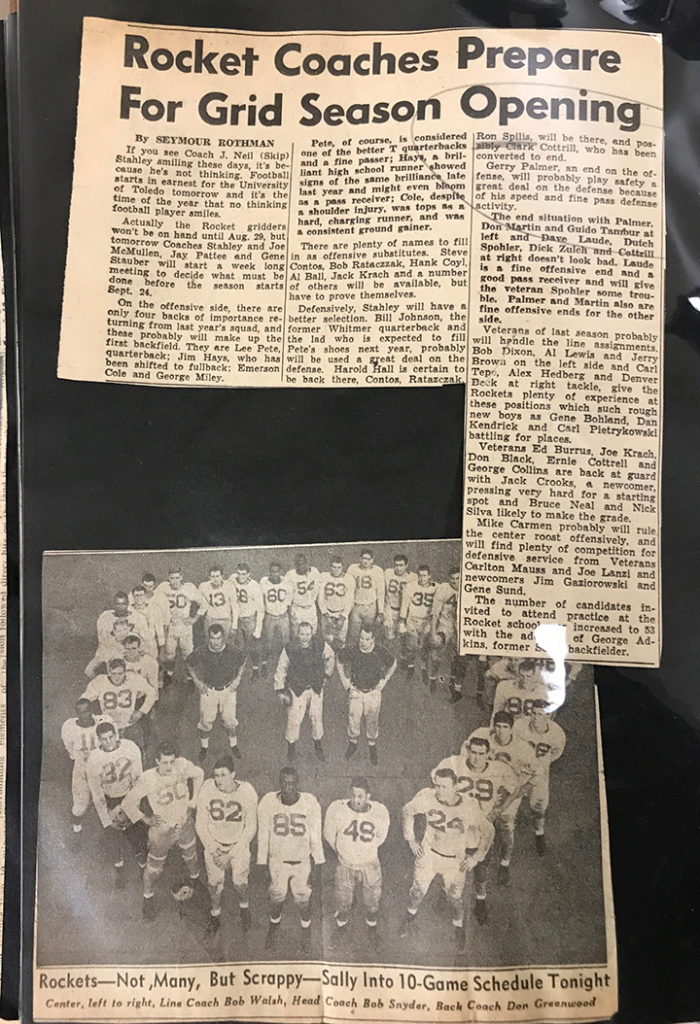

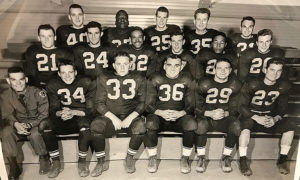

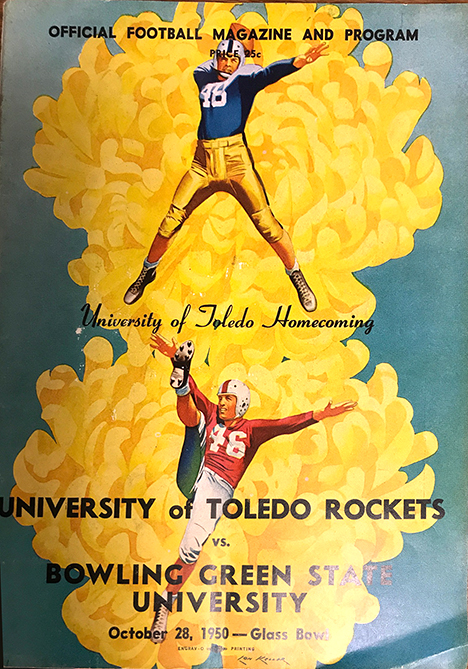

Healed and healthy, the grid iron was calling. It was 1949, and Toledo’s head coach was Skip Stahley. “A lot of men on the team were from service, from WWII, who were really big people. We had about 40 players,” says Spilis, who wore the No. 49 jersey.

In the early 1950s, Americans were experiencing a baby boom, an increase in consumer goods and suburban living, as people moved out of cities. And simmering beneath the surface of the American Dream was civil unrest, as more African Americans challenged the prevailing racial discrimination, mainly in the South. African-American football players, including TU Rockets, felt the sting of racism.

“I didn’t feel comfortable with it, but I grew up in a period of time when that was in existence, that particular mindset. It’s a shame, but it’s something that occurred.

There’s been a drastic change. I remember two or three teammates who were very excellent players who were black.” Emerson Cole, Clark Cottrill and Jerry Palmer were esteemed by teammates, he says. “The three players I mentioned, they had respect.”

Newlyweds and G.I.s

At that time, life was like a waiting game. He waited for the next time he’d see his girlfriend, Florence, in Toledo, and he and the other Fort Riley infantrymen knew their time would come to be shipped out. “I was going with a girl at the time, my wife-to-be, and they gave us a 30-day leave.” Spilis and another Toledoan at Fort Riley drove back to Ohio. “I got married two days after Valentine’s Day, Feb. 16, 1952,” he says. The couple celebrated 65 years of marriage this year.

They honeymooned in Michigan and then took a train from Chicago to Seattle, where they stayed off base before Ron’s deployment. “Uncle Sam paid for the trip. We were there about a month, until they got all the troops together. We left Seattle and landed in Yokohama, Japan.”

While Florence was back at home in Toledo, working at Tiedtke’s department store and living with Ron’s parents, Ron was landing in Incheon, South Korea, where he was assigned to Company A of the 17th Infantry Regiment. The young draftee, who would never have signed up to go into the military, bravely served in Korea instead of considering the option to join the ROTC.Referred to as “The Forgotten War,” the Korean War was, at first, considered a “conflict,” or “a police action,” to use President Harry S. Truman’s term. The American public, especially liberals, were more concerned with “McCarthyism,” and opponents of the Korean War were at a minimum — unlike the number who would oppose America’s next “conflict,” the Vietnam War.

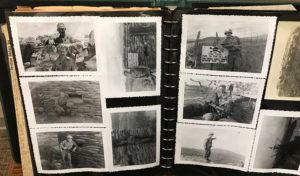

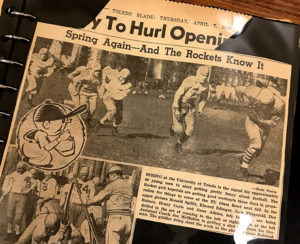

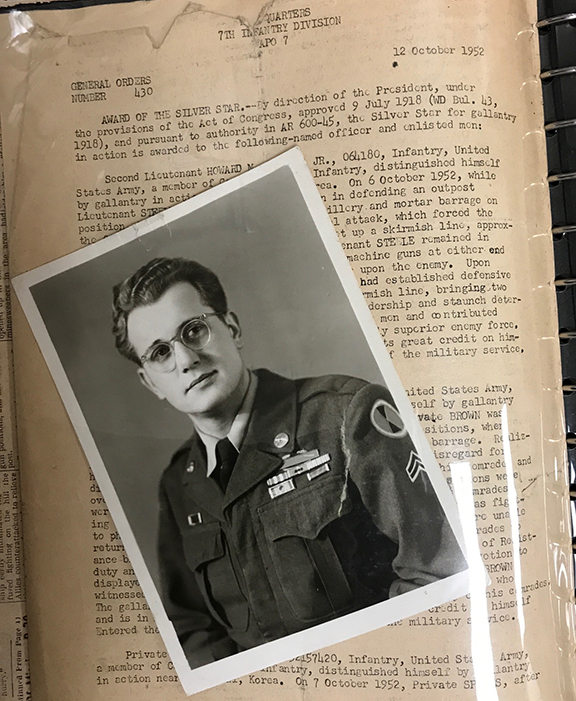

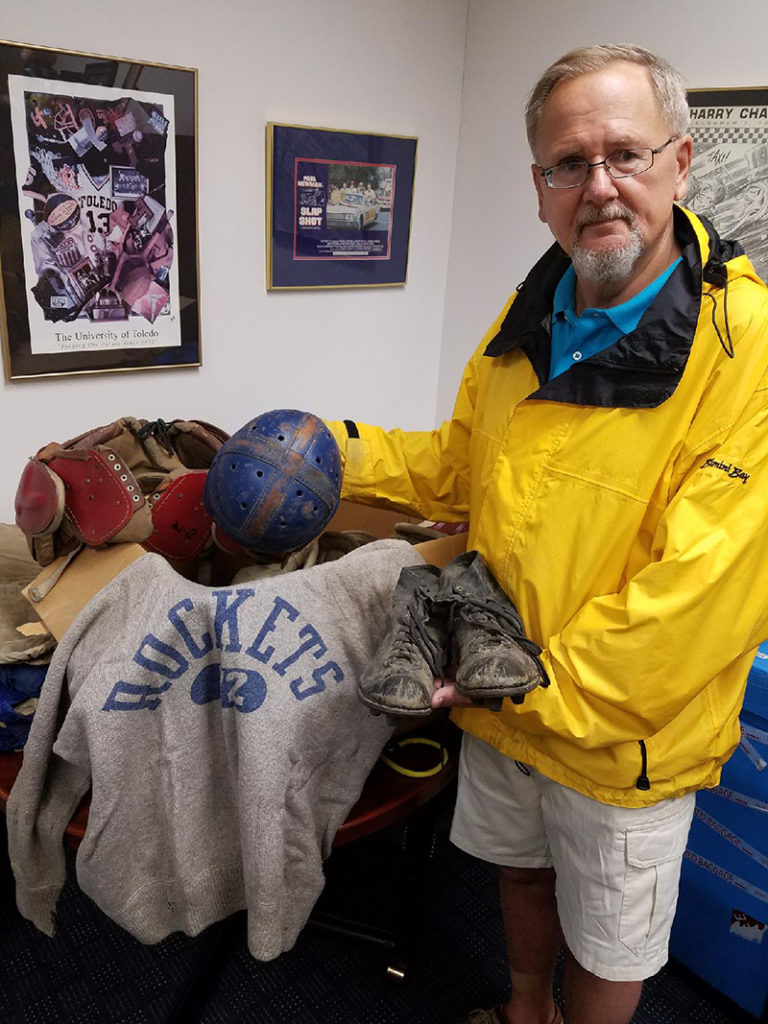

Fear, Courage and Survival Between the cover of an old green photo album, Spilis keeps his football memories. Inside, the pages are filled with team rosters, football plays drawn on discolored paper, photographs and game programs.

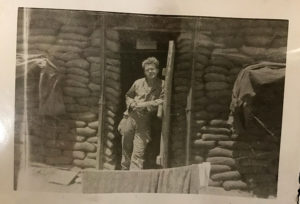

Among those sports memories are Spilis’ connections to his time spent in Korea with many other men in their early 20s who fought on the frontlines defending South Korea. On these pages, a youthful Spilis is seen in black-and-white photos standing in front of a bunker, getting a haircut by a fellow G.I., posing on a ship with a cigar, leaning on a post near a bunker that warned of the MLR, the main line of resistance.

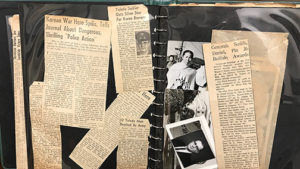

Yellowed newspaper clippings recall the story that Spilis had told multiple reporters about the day he became separated from his platoon after mortar shells interrupted the troops’ meal. Running through trenches, he ran into a bunker where he hid on the top bunk, facing the exterior. Spilis waited quietly as three Chinese soldiers entered the bunker. One Communist soldier sat on the lower bunk to assess a wound, as another helped administer first aid to the wounded soldier. The third man glanced over to the top bunk and spotted Spilis. He grabbed for his burp gun, but Spilis quickly responded with a 45-caliber pistol that he’d taken off a dead soldier in a trench. He shot at the Chinese soldiers. Two fell at the entrance of the bunker as the other fled.

He made his way out of the bunker but couldn’t find anyone in his platoon. As he pressed himself up against a bunker doorway, amid gunfire, he finally heard voices and someone yelled out, ‘G.I.,’ and he answered. Spilis reconnected with members of the relief force, helped them with the wounded, and then was ordered back to the main positions. Spilis received the Silver Star for this harrowing experience. He says all he could think about was Florence and his unborn child who was on the way. “I thought about survival.”His son, Michael (Bus ’74), was born on Dec. 3, 1952. Spilis received the news four days later in a cable message from the American Red Cross. He was discharged from the Army in July 1953, but not before going AWOL. Spilis says he had forgotten about the time changes when he reported to Fort Indiantown Gap in Pennsylvania. “I got back to camp 15 hours late, so I was AWOL, and they took my stripes away. I said, ‘Go ahead and keep them,’ but I got them back. I said, ‘Give me my papers so I can leave.’ I was obnoxious,” he says.

Back to the Future

“I got a job as an industrial engineer, in Monroe with Ford, until I was transferred to industrial relations. I had the chance to go to Lima as a safety engineer with the intention to go into personnel benefits.” While working for Ford in Lima, Spilis thought a PhD would add to his resume. “I decided I wanted to go for my PhD at Wayne State University. I took all my credits there, and I was there for about three semesters.” A language requirement and the commute to Toledo changed his mind about continuing that pursuit.

Eventually, Spilis left Ford during a big layoff. He worked at a few other jobs, including Champion Spark Plugs. “I did some consulting work in the city of Toledo in labor relations.” After five years with the city, Spilis retired. Florence was working for Ford and retired from the central office in Dearborn, Mich.

During his time on the team, Spilis says the Rockets’ record was average. “When they had more of the WWII vets, they had more dedicated, experienced players, and they had a better record.” Perhaps the lessons learned on the battlefield made the veterans tougher on the football field.

If Spilis had gotten a second chance to play for the Rockets when he returned from Korea, he might have earned that varsity letter. But even though he did not play football for the Rockets again, his valor in Korea saved his life and earned him an important place in history. He doesn’t show off his medals of honor from the military, and he says they’re framed only because Florence insisted. “I hide this behind the TV. I don’t like to talk about them. I’ve never worn them; only when I got them, that was it. It’s history.”

Earlier this year, George Pugh and Andrew Fisher, two local men who are collecting stories of war veterans who live in northwest Ohio, interviewed Spilis for the Veterans History Project of the Library of Congress. The project was created to ensure that those who fought in wars are not forgotten.